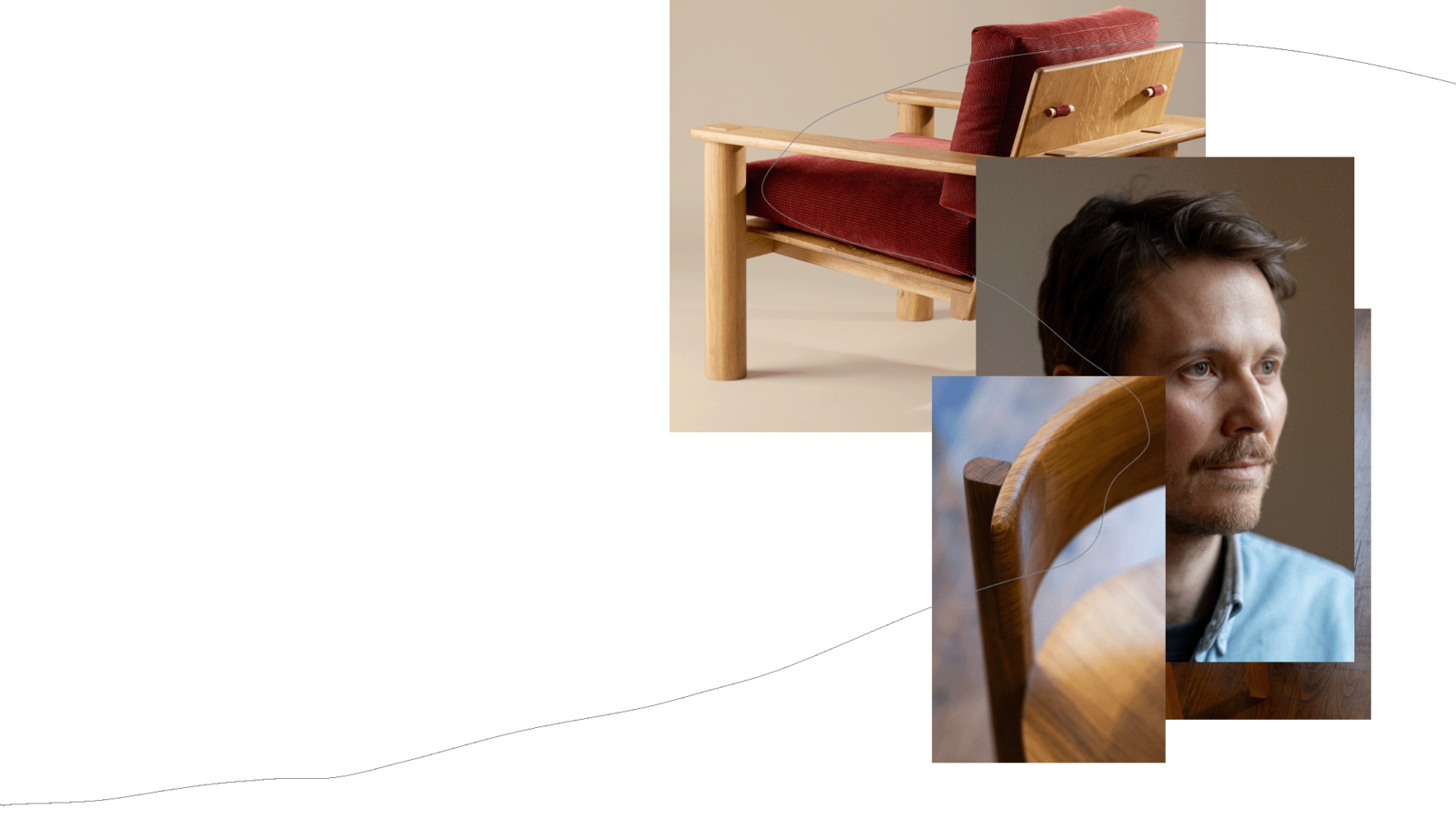

L’établissement: A successful woodworking reconversion

Meeting with Quentin Pigeat—an architect turned woodworker, the founder of “L’Établissement” explains the why and how behind his recent career transition

Version Française (originale)→

You have a background as an architect working on large-scale renovation projects, and today you are a woodworker and designer of contemporary objects and spaces. Can you explain what motivated this career transition?

I spent the last six years of my career as an architect at François Chatillon, managing complex, high-constraint projects. I was particularly involved in the renovations of the Cité de Refuge (Le Corbusier), the Amiraux swimming pool (Henri Sauvage), and the restructuring of the Carnavalet Museum.

However, I felt the need to reconnect with a more direct creative process, one that wasn’t stretched out over long periods. Architecture follows a slow rhythm, requiring numerous adjustments before reaching realization. I wanted a more immediate connection to materials and fabrication, which ultimately led me to change paths.

What skills from your career as an architect do you still use in your current work? And on the other hand, are there any aspects of architecture that you miss?

I would say I’ve transitioned into two professions: design and woodworking craftsmanship. Architecture gave me the tools to create, solve problems, and manage constraints. Today, those skills are just as valuable in both the design and fabrication of objects. My eye is always engaged—evaluating proportions, balance, and composition. My past experience has been essential to my work. As for what I miss, I don’t feel a sense of loss at the moment, but I would be interested in revisiting spatial design in the future.

So, it seems like there’s a shift in the balance between creativity and problem-solving, with the creative aspect now taking up more space than the technical and constraint-driven side?

Yes. In architecture, managing constraints often takes precedence over creation. Today, even when technical challenges arise, they are more tangible and immediate—how to assemble these pieces? How to achieve the right finish? In the workshop, I’m constantly designing new pieces. As soon as an idea emerges, we bring it to life quickly, and new questions naturally follow. It’s a more fluid, instinctive process.

After your experience at François Chatillon, you trained with the Compagnons du Devoir. During that time, you honed your skills at Atelier de la Boiserie, where you stayed for a few additional months. Can you tell us about this transition? Why did you choose the Compagnons du Devoir? And what drew you to training at Atelier de la Boiserie, a workshop known for its meticulous craftsmanship, even though its style is quite different from what you do today?

The Compagnons du Devoir was an obvious choice—it represents excellence and offers a hands-on, apprenticeship-based learning approach. A close friend had trained there, and I quickly realized the value of experimentation and the repetition of gestures in mastering the craft.

I first discovered Atelier de la Boiserie while working on the Carnavalet Museum restoration. I had already seen the quality of their work firsthand. There, I learned the discipline and precision required in woodworking. Even with simple tasks, striving for perfect execution builds true mastery.

This transition obviously involves a shift in scale, moving from buildings to objects and furniture. With this new direction, you had the option to work with various materials for industrial design. Why did you choose wood as your primary material?

It felt natural. I love its texture, the way it comes together, and the process of assembling it. I also enjoy working in the workshop—there’s a structural logic to it that resonates with me as an architect.

That said, I’m not limiting myself to wood. I’m open to exploring other materials in the future, and the workshop is already set up for experimentation beyond woodworking.

“It’s important to fully commit to what you do while also finding the balance between impatience and the time required for ideas to fully mature”

People say you love to draw. Can you tell us about your creative process, from the initial concept to the final piece? How do the execution and production phases unfold?

Everything starts with drawing, often in axonometric projection. Recently, I’ve reintroduced scale models into my process—they help me better understand volumes and experiment freely. This approach also allows for a more exploratory, open-ended process, where unexpected ideas emerge through the model-making phase. My worktable is always covered with scraps, dowels, and rods—it’s become almost like a construction game where new ideas take shape.

This process will actually be showcased at the Biennale Émergence. But I want to keep evolving it by incorporating other materials, so I’m not limited to forms dictated solely by wood.

Do you prefer working with physical models over 3D modeling? Does 3D play a role in your creative process?

Before fabrication, I work on plans, sections, and elevations digitally. To refine proportions, I turn to physical models, but there are always final adjustments at full scale. I occasionally use 3D modeling, but I prefer drawing and direct fabrication.

Regarding the production phase—after all the design and model-making—can you tell us about the tools you use and your relationship with them, whether hand tools or machines?

At first, I wanted to do everything by hand to prove my craftsmanship. Over time, I’ve gained confidence and now prioritize stationary machines for their precision. Efficiency is essential—you have to produce and move forward.

Your designs are remarkably refined and intentional. They feature pure, geometric lines while maintaining a soft aesthetic through harmonious curves. What stands out is the balance between highly sophisticated joinery and clean, minimalist forms. Can you tell us about your influences and how you developed such a distinct and personal style in just a few years?

At first, my references were quite classic: Pierre Chapo, Charlotte Perriand, Nakashima… But my perspective has expanded. My colleague Jonathan Cohen introduced me to the Memphis movement, and Instagram exposes me to a wide range of sculptural approaches.

I’m leaning toward more minimalism. In the past, I wanted to showcase every joint and connection. Now, I refine my intentions more, aiming for a balance between technique and aesthetics.

There’s also a subconscious interplay of influences. Today, we see hundreds of images a day on Instagram. It’s crucial to fact-check ourselves when designing—to ensure we’re not unconsciously replicating something we’ve seen. It happens: you think you’ve come up with a new idea, but you have to verify that you’re not just distorting something you’ve absorbed elsewhere. That’s the risk of being overexposed to visual content.

Shifting the topic slightly, your work is backed by a strong visual identity and branding. How do you approach this aspect? You’ve mentioned that you’re increasingly handling it yourself. What drives you to give it so much importance?

Photography has always been a big part of my life. Back in high school, I set up a darkroom in my bathroom. At the time, I was passionate about documentary photography, whereas now I focus on still life. It’s an interesting part of my work, even if it can be demanding.

Today, I handle my own visuals—clean product shots and spontaneous photos in the workshop, which benefits from ideal natural light. This approach works: it attracts ambitious projects and helps me define my identity.

What does the future hold for Quentin Pigeat in the medium and long term? Where do you see yourself in 5 to 10 years?

In the short term, I’m working on the renovation of DIVISION’s offices in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris, designing large custom tables and interiors in collaboration with Atelier MAS. I’m also participating in the Biennale Émergence this April.

In the medium term, my business is growing. Architecture firms are starting to recommend me, opening exciting new opportunities for 2025.

With this rapid growth, how do you see the future? Would you rather keep a small team of two or three people in the workshop, or expand into a larger structure?

For now, I bring in external help for large projects. If growth continues, I’ll strengthen the team internally. But my priority is to maintain a balance between production, creativity, and the enjoyment of the craft.

To wrap up, what advice would you give to your 10-year-old self?

There are things I only understood later in life. Open-mindedness and curiosity were natural qualities for me, and they’re values I now try to pass on to my children. Discipline is also key—you need to create the right conditions to pursue your ambitions. It’s important to fully commit to what you do while also finding the balance between impatience and the time required for ideas to fully mature.